Indeed, Žerajić’s failure to fire would become a nonevent of such great pitch and moment that it inspired one of the signal events of the 20th century-the Sarajevo assassination.Īs every European history textbook teaches, on June 28, 1914, a young Bosnian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, in Sarajevo. What makes Žerajić’s inescapably unheroic attempt on the kaiser’s life unusual for a nonevent is that it bridges both these definitions: it didn’t happen (i.e., he never drew his revolver, let alone drew attention to himself as a suspect assassin) and later memory made it more than it ever was. Many of history’s seemingly heroic episodes, like the Bolsheviks’ “storming” of the Winter Palace (or, more accurately, its wine cellar), have similar lineages. Mussolini’s 1922 “march on Rome,” where Il Duce arrived by train to tranquilly receive the king’s consent to form a government, only became a dramatic “event” through later fascist propaganda. This can also work in reverse: our instinctive need for decisive moments in history to be appropriately “eventful” often affects how we remember them. In the latter case, like a highly anticipated diplomatic summit in which nothing serious gets resolved, a nonevent may be an actual event that’s less exciting, or “historic,” than expected. The term nonevent can be understood in two ways: the obvious sense of something that simply did not happen and the more commonplace usage of an anticlimactic occurrence. It was just one of several attempts on the kaiser’s life that failed to materialize or just failed altogether. It was the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen. Although security was far heavier than it would be when Franz Joseph’s nephew and successor, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, made his infinitely more infamous visit to Bosnia and procession through Sarajevo four years later, an armed nationalist named Bogdan Žerajić had twice gotten so close to the kaiser that, as he despairingly told a friend, “I could have practically touched him.” Yet out of some combination of fear and fecklessness, the Bosnian student never pulled the Browning pistol from his pocket.

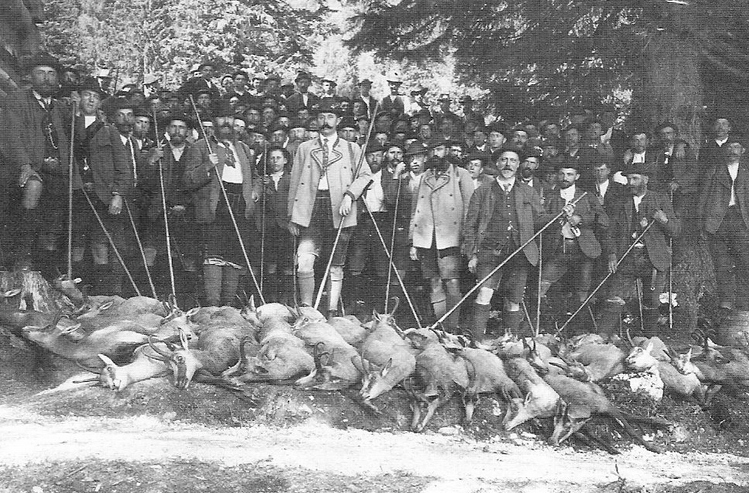

In fact, it nearly ended his life more than six years prematurely. Courtesy Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. By all accounts, the 79-year-old emperor of Austria and king of Hungary so thoroughly enjoyed himself in his southernmost Slavic domains that, at one point, he turned to his host, Bosnian governor-general Marijan Varešanin, and exulted: “I assure you, this voyage has made me some 20 years younger!”Įmperor Franz Joseph processing through Sarajevo on May 31, 1910, the day of the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen. Yet no bombs were hurled at him by Bosnian or Serb nationalists, no bullets fired at his regal presence in the empire’s newly annexed province of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Franz Joseph’s visit was thus a political affront and a perilous act. Although the Habsburg monarchy had administered Bosnia-Herzegovina since 1878, the Kingdom of Serbia coveted the adjacent, south Slavic region as its rightful irredenta, and Russia backed Belgrade’s national ambitions in the contested Balkans. Barely a year earlier, the Bosnian annexation crisis had nearly sparked a European war. On the blustery afternoon of May 31, 1910, Habsburg emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary peacefully paraded by horse-drawn carriage through the crowded streets of Bosnia’s capital city, Sarajevo.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)